Introduction

If you’ve been practicing piano and find that you’re plateauing, a simple change in approach can get your progress moving forward again and reinvigorate your passion for piano. Effective practice isn’t about how long you sit at the piano, but how you spend that time. This guide outlines practice techniques that will help you achieve the results you are seeking.

Whether you’re a beginner needing first-time guidance on practice, or a seasoned pianist looking for a different perspective, this guide has something for everyone. We cover everything from setting up an ideal practice space and specific approaches for learning efficiently, to methods for keeping track of your progress and staying motivated.

Section 1: Setting Up

Your Piano and Bench

You want to have the right piano for the job. Most beginners start on a digital piano. This is perfectly fine; however, even as a beginner, you’ll want to have a full-size keyboard (88 keys) with weighted keys (which imitates the hammer action of an acoustic piano). Avoid keyboards with the flimsy, plastic keys – they’re not good enough to play on. It’s important to get started with a true piano, so you can get used to how the keys feel under your fingers, and to be able to play dynamics (loud and soft sounds).

Use an adjustable piano bench for practice. Do not use a dining chair, a folding chair, or a chair with wheels. Bench height has a surprisingly profound effect on your comfort level at the piano. I’ll quote from a previous post:

To determine proper bench height, place your hands on the white keys. Your elbows should be in line with or slightly above the surface of the white keys. For proper bench distance, make a fist with a straight arm (don’t bend at the elbow) and place it on the keys. Your fist should reach the back end of the piano keys. Adjust accordingly if this is not the case.

By positioning your bench at the proper height, your arm is balanced as you play – your wrist and elbow will be taking equal weight. By giving yourself enough distance from the piano, you can easily access the entire breadth of the keyboard.

Distraction-Free Space

Make sure your piano is in a quiet room, free of distractions. Don’t have the TV on while you’re practicing. Put your phone on silent, or better yet, keep it in another room. If possible, have your practice space be in a room where you have some privacy and can shut the door. If not, use headphones – they’ll block out external noise and give you an internal sense of privacy while you practice.

Section 2: How to Practice

Be Consistent

Consistency is arguably the most important driver of progress. Regularly sitting down at the piano to play will help you become more comfortable and more familiar with all aspects of piano playing: note reading, keeping a steady speed, and the coordination between reading and physically playing the piano all become easier the more often you sit down and play. Make playing piano a ritual; at best, it will become one of your “happy places” – a place to unwind. Yes, practicing piano can be a relaxing activity!

Aim for playing the piano at least four days a week – but if you can bump it up to six days, or every day, that’s even better. As a beginner, practice sessions of twenty minutes are perfectly fine. The length of your sessions will increase as you gain skill and the material becomes more complex.

It’s important to spread out your practice. 20-minute practice sessions spread over four days are more beneficial than one marathon session of 80 minutes. The spread-out sessions allow for greater absorption of information and sustained concentration on the material. Crucially, what you’ve learned in the practice sessions will be stored in your long-term memory. With spread-out practice, you’ll have an easier time retaining what you’ve learned by repeatedly returning to it. You won’t have this benefit with a single “marathon” practice session – you’ll forget what you’ve learned over the course of the week, and your concentration will start to lag even during the long practice session.

If you are at an advanced level and are practicing for an hour or more, the Pomodoro technique may be beneficial for you: 25 minutes of work, 5 minutes for a break, and repeat. Try different approaches to practicing and taking breaks in order to “refresh” your mind and maintain focus – you’ll find what works for you.

Set Goals

Setting goals gives you focus, discipline, motivation, and a milestone to strive towards. It also holds you accountable; if you set a goal, you will know whether or not you achieved what you set out to do.

Set short-term and long-term goals. Short-term could be a goal for a single practice session. Some examples:

- Play the piece at a steady speed (doesn’t matter how slow)

- Learn all the dynamics

- Have all the correct phrasing and articulations (staccatos, accents)

These are goals that can be achieved within a single practice session. If you don’t completely achieve a goal you set out for a practice session, acknowledge that you have made progress on it – which is a success in itself. You can complete your goal next session.

Long-term goals are those that make take several weeks or months to achieve. For example, some long-term beginner goals could be:

- Finish half the method book in four months (adjusting the time frame as needed)

- Easily identify all the notes on the grand staff within the lines and spaces (use note identification drills to test your knowledge)

Long-term goals for more advanced students could be:

- Learn an entire Beethoven sonata in six months

- Be able to improvise in any key

These goals can be adjusted as needed. It’s also important to set realistic goals. You want to strive for success; if you set yourself a goal that’s too difficult for your level, you may end up demoralized when you don’t achieve it. Be sure to discuss your goals with your teacher, as they have a greater level of experience and can help you adjust your expectations to a realistic level.

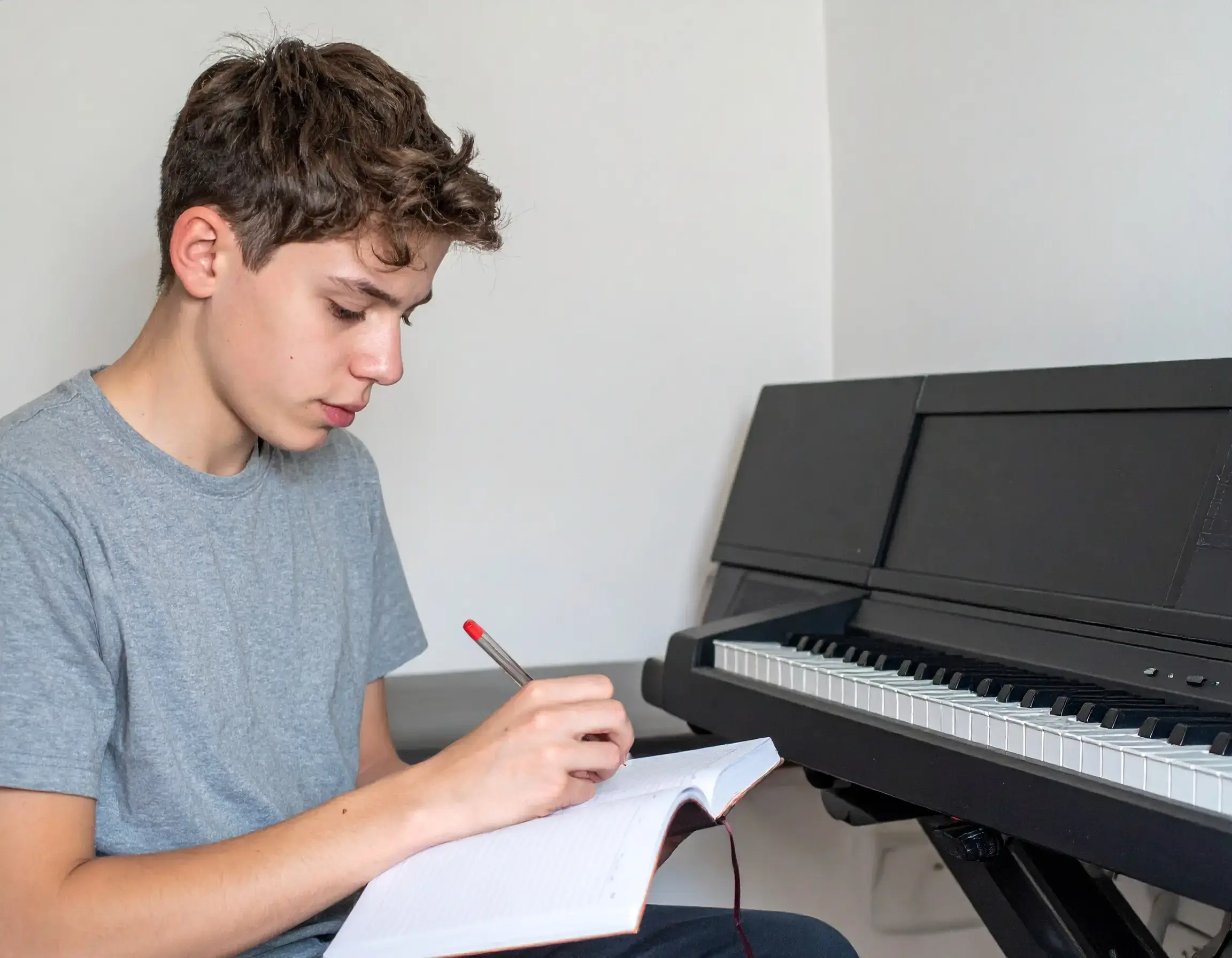

Keep a Practice Journal

An effective way to keep track of goals is to keep a practice journal. Write down your goals for a practice session, then when it’s complete, write down what you completed. This can be very useful for short-term goals that were only partially completed; you don’t have to keep track in your head of what you did and what you have to do next time; you can simply consult the journal.

One of the greatest benefits of a practice journal is that you have a clear timeline of your progress and successes. Look through the previous entries practice journal after a few weeks, or six months, and see how far you’ve come! It can be a great opportunity to celebrate your successes and pat yourself on the back.

Learn Notes and Rhythm Simultaneously

You want to place a piece correctly from the outset. Therefore, you must learn the correct notes and rhythm at the same time. If, for example, you only learn the notes correctly first, paying little attention to the correct rhythm, you are adding extra work for yourself later by undoing your familiarity with the incorrect rhythm and relearning properly. Moreover, you reinforce a bad habit: one of learning notes and rhythm separately. You will seriously hinder your progress if this is how you learn new pieces.

So how to learn notes and rhythm at the same time? Play as slowly as needed to achieve accuracy for notes and rhythm, and to keep a steady tempo. This way, you are building a solid foundation for when you take the piece at a faster tempo later on. It’s a highly effective habit that will pay huge dividends as you graduate to more complex pieces.

Keep a Steady Pulse

The steady pulse is a “heartbeat” or “throb” in your mind which you follow while you play, in order to establish a consistent tempo. It’s the same feeling as when you’re tapping your foot to a song you’re listening to; your tapping just falls into step with the beat, and you don’t really have to think about it. The steady pulse should be just as stable, but you are conjuring it within your own mind.

We all have a heartbeat, so we can all keep a steady pulse. As mentioned in the previous point, play the piece slowly enough so that you can get the correct notes and rhythm while keeping the steady pulse. Remember that the pulse is in charge: the notes follow the pulse, not the other way around.

Hands Separately, Hands Together

What to do – play the piece one hand at a time or hands together? The answer is: it depends. When you are first starting out, especially with a method book, your very first pieces are usually hands separately. This will help you get your bearings at the piano. Once you reach pieces that involve the hands playing simultaneously, they will usually be simple enough that you can play hands together right away.

I often recommend sight reading a new piece hands together – even if it feels tough, with much hesitations and pauses. The reason I think this initial run-through is so important is because it helps you orient yourself within the piece – you get a very clear idea of where the challenges are, and what you are up against.

However, if the piece poses a great challenge hands together, practice hands separately after your initial reading. Familiarity with the music in each hand will facilitate the coordination required when playing hands together.

Also worth noting: don’t practice hands separately for weeks and weeks. Make regular attempts at playing hands together. Your goal is to play the piece hands together, so get there as soon as you can. If you find a passage is causing you difficulty hands together, slow down, and if that doesn’t work, check to see if it flows smoothly hands separately. Then you can assess whether you need to play hands separately a few times, or if you have to play even slower hands together to achieve the proper coordination.

Practice in Sections

Divide longer pieces into manageable chunks. These can be phrases of four bars (or measures), eight bars, or other configurations. Sometimes you can do a single line of music. Sometimes you might need to work on just a bar or two. The point is that practice is the time when you can split up the piece, improve on parts here and there, and then put the pieces of the puzzle together.

When in throes of learning a new piece, especially a longer one, our focus will lag if we simply toil and stumble through the entire piece from beginning to end. We will miss important details, as well. Practice is a place of discovery, analysis, and experimentation. Try different expressive approaches, solidify your technique, and refine passages. Stay curious and strive towards your goals. Practice is not performance, it’s time for you to get to know the piece. Breaking down the piece into manageable chunks is an essential method for truly mastering a piece.

Play Slowly (At First)

I’ve already mentioned this a few times. When learning a new piece, you need to have a solid foundation. You need to feel confident and certain about what you’re playing. Simply put, you need to know it. This means that you should only play as fast as you can think. So, when learning a new piece, play slowly. This will also ensure that you feel relaxed when you are playing piano – a very good habit to build up.

If you choose a tempo that is too fast for you, you will not only make mistakes, you’ll feel anxious and won’t have time to think about what you’re doing. This will hinder your progress. Be patient and practice at manageable tempo – with familiarity, the speed will come.

Be Mindful of Technique

Technique (the way in which you use your arm, hand, and fingers at the piano) has a direct bearing on the quality of sound and expression you convey at the piano. Having a teacher who teaches proper technique is essential. There is a correct way to get the sound out of the piano.

Some guidelines: use arm weight to “sink” into the key (rather than using only your fingers to press the key); let the wrist move freely as you play; use wrist bounce for detached notes; use forearm rotation for connected notes; and don’t dig into the key.

Proper technique will increase your longevity at the piano, and making playing literally everything easier. With proper technique, playing piano doesn’t feel like physical effort; it feels weightless – yes, really!

Consult a teacher or video tutorials for visual demonstrations of technique; such demonstrations and further explanations are essential to truly understand the motions, gestures, and sensations you are trying achieve while playing.

Practice Away From the Piano

Imagining yourself playing piano can be an effective supplement to your practical practice in front of the piano. Visualize the keystrokes and hear the music in your mind. Mentally walking through the piece in this way will reinforce your knowledge of the music.

Studying the score away from the instrument is another effective tool. Here, again, you are hearing the music in your mind while imagining yourself playing. When you reach a difficult passage, notice what happens in your mind – are you still able to clearly visualize what you would play on the piano? Also notice what reactions occur in your body – are you tensing up? This is a signal to familiarize yourself even more with that passage. Play it slower in your mind, and clearly imagine how you will play the passage. Choose a speed where you feel relaxed. This will help you feel more prepared when you return to the piano to play the passage.

Listening and analysis is another tool. Listening to a recording of the piece while following the score. Notice the phrasing, dynamics, rubato (slight alterations in tempo), and expressive choices. This will provide you with insight into how the music can be shaped, will give you some ideas for your own expression, and help you get even more familiar with the music.

Of course, nothing takes the place of physical practice. But mental practice is an effective supplement – it gets you thinking about the music in a different way.

Section 3: Staying Motivated

Track Your Progress

The aforementioned practice journal is an easy way to keep track of your progress. You can check it and update it at the beginning and end of your practice sessions, and you can look through to see how far you’ve come.

Another way to track your progress is to occasionally record yourself playing your piece. Recording yourself helps you ascertain what works well in your interpretation, and it can also reveal parts to improve upon that you may have not been aware of. Additionally, comparing recordings taken a few weeks apart from each other is an illuminating way to listen to how your interpretation has improved.

Share Your Successes

Don’t be afraid to play your piece for others – they would love to hear you play! If you can get through your piece pretty smoothly, a few mistakes here and there won’t matter. You’ll be surprised at how playing a piece successfully in front of others can boost your confidence.

Conversely, if you play for others and the piece falls apart, don’t despair. Your success here is that you did something brave: you performed in front of others, and that always deserves respect. You know what to improve upon for next time. Don’t give up!

If you know other musicians, share what you’ve been working on and ask for advice. A sense of community can be truly motivating in keeping up with your practice.

Change Things Up

Sometimes you just need a break from a piece you’ve been practicing. If you’ve been working on a piece intensively, and you feel yourself getting tired of it, take the pressure off yourself: put it aside for a few days and learn an easier piece, perhaps in a different genre. A shift in mood and perspective will help you come back to the piece with fresh ears.

Of course, if you have an upcoming performance in a few days, now is not the time to put the piece aside. Continue to practice your piece, but still, unwind by playing other music you like that you have no pressure or obligation to refine and make performance-ready. You want to maintain a sense of “play” when playing the piano.

Set Performance Milestones

Performances are a great opportunity to test how well you know a piece. The deadline serves as an impetus to refine a piece to the best of your ability. But best of all, performances are an opportunity to share music with others.

Even if the idea of performing scares you, go for it. By performing in front of an audience, you learn a lot about yourself, and you build resilience. And when you succeed at a performance, you will feel not only your self-confidence as a musician increase, you will feel the joy of having shared music with others, and the mutual appreciation between the audience and yourself will buoy you.

If you’ve prepared yourself and practiced sufficiently, you have a high chance of succeeding if you just give yourself to the moment and let the music speak through you.

Practice Self-Compassion

We all have bad days. There will be days where you’re not feeling it, you’re not motivated to practice, or you’re making more mistakes than usual. There may be days when you get down on yourself, hurling virulent insults at yourself such as: “I’m not a virtuoso yet! Therefore I’m completely trash at piano!” – I’m exaggerating here, but my point is this: banish the negative self-talk. Negative self-talk is hyperbolic: all-or-nothing thinking, discounting any positive qualities you possess, downplaying any successes you have achieved, and so on. Essentially, the negative self-talk is a lie that you tell yourself. So take a couple of deep breaths, step away from the piano, and rationally debunk these statements you’re making about yourself.

Take a look at your practice journal to remind yourself of how much progress you’ve made; or listen to a recording of yourself that you’re particularly proud of. If you’re up to it, you can even play something on the piano that gives you sheer joy, without any pressure or self-judgment. Just choose to do something that lifts you up and reassures you, like a good friend would.

If nothing feels like it’s going right during practice, and you’re self-flagellating yourself into continuing, despite a growing sense of despair and burnout, it might be a good time to just step away; take the rest of the day off and do something else you enjoy.

Above all, be kind to yourself. Be gentle with yourself. Playing piano is not a chore or an obligation; playing piano is an expressive activity, and a leisure activity. The things we do for fun count for a lot towards our emotional and mental well-being. So don’t be so hard on yourself; this is supposed to be fun, a journey of discovery, a place to stay curious, a place to express ourselves.

If you lose sight of the expressive and joyful aspects of playing piano, and get too caught up in completing tasks, being productive, you miss out on the fun of it. We want to balance striving forward and making progress with the pleasure of expressing ourselves through music. And you don’t always have to practice when you’re at the piano: sometimes you can just go and play a piece you’ve learned, or improvise, and have fun.

Uplifting self-talk, allowing yourself to take breaks, and approaching piano with a sense of play are all acts of self-compassion that can enhance your experience of learning the instrument, and will help make playing piano not just a joyful activity, but a peaceful one. Music nourishes the spirit, as does treating yourself with kindness.